Revelation 6:5-6, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Part IV of V

When the Lamb opened the third seal, I heard the third living creature say, “Come!” I looked, and there before me was a black horse! Its rider was holding a pair of scales in his hand. Then I heard what sounded like a voice among the four living creatures, saying, “A quart of wheat for a day’s wages, and three quarts of barley for a day’s wages, and do not damage the oil and the wine!”

//Continuing our discussion of the four horsemen and how they relate to the events of the first century, we come now to the color black. As expressed by Jeremiah, the black horse brings famine. The famine during the Jerusalem war grew so devastating that at one point, a woman named Mary boiled and ate her own son.

The words this horseman speaks are fascinating. Read them again, and compare them to what first-century Jewish historian Josephus reports of the Jerusalem war: “Many there were indeed who sold what they had for one quart; it was of wheat, if they were of the richer sort, but of barley, if they were poorer.”

Revelation later bemoans how the merchants profited from this wheat, olive oil and wine. This unnamed voice that says “do not damage the oil and the wine” for some reason makes a deep impression on Revelation’s author. No surprise: When General Titus captured the Temple in the war of 70 A.D., he gave explicit orders not to destroy the oil and wine in the Temple so they could be retained and sold to the rich.

Book review: The Gospel of Mark as Reaction and Allegory

by R. G. Price

★★★★

This book provides an excellent collection of Markan midrash, going verse-by-verse through Mark and explaining its sources. Mark pulls his stories of Jesus from Isaiah and the prophets, and Price makes an excellent case for Mark also borrowing from the writings of Paul. Price also points out the influence of the war of 70 CE upon Mark’s Gospel, a topic I discuss in my book about Revelation, but not to the depth of this book. It is my opinion that this “war to end all wars” is too often understated in Gospel analysis, and Price’s analysis should contribute to scholarship on the topic.

The book’s stated purpose is to show that the Gospel of Mark was written as an allegorical study in reaction to the destruction of Judea in 70 CE, the intention of which was to portray Judean Jews as having brought that destruction upon themselves. In this, Price proves his point very well, though it may be optimistic to conclude, as he does, that this is the primary intention of the Gospel. A secondary purpose of Price’s book is to show that there is no flesh-and-blood “Jesus” beneath Mark’s midrash. Of this, I came away a bit unconvinced. Although Price does highlight the dependency of Mark upon earlier Christian (Pauline) writings, he does not take the second step of proving that Paul, himself, was never writing about a flesh-and-blood Jesus. However, I confess I read Price’s books out of order. I suspect his treatment of Mark builds upon a foundation laid in Jesus: A Very Jewish Myth, which I haven’t yet read. So, while there are a number of other reasonable conclusions I could draw about Jesus’ historicity from Mark’s Gospel alone, that topic will wait until I’ve read more of what Price has to say.

But whatever the reason for Mark’s parallels to other scripture, those parallels do unquestionably exist, and scholars are right to wonder why. This book’s conclusion details a very interesting scenario about how the Synoptic Gospels were derived. Hint: No “Q” gospel. Price touches lightly upon the possible derivation of John’s Gospel as well, but on this topic, he and I are at odds: I think he neglects evidence of Johannine familiarity with Judea, instead portraying the Fourth Gospel as the creation of an anti-Jewish Gentile, and I think he overlooks evidence of John’s dependence upon Pauline theology. But John’s Gospel is ancillary to what Price does do very well, and that’s to lay out plausible origins of Synoptic thinking.

If I have one complaint, it’s that the scriptural references could be condensed. Often, I found myself reading long passages in Old Testament references where it seemed that a single verse or two would be sufficient. In retrospect, I realize Price wants us familiar with the settings of these stories, so that we’ll recognize Mark’s many allusions to passages that deal with the destruction of Jerusalem. So, I’m warning you of this up front; if I had understood his purpose, I would have paid more attention to the lengthy references.

Revelation 6:3-4, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Part III of V

When the Lamb opened the second seal, I heard the second living creature say, “Come!” Then another horse came out, a fiery red one. Its rider was given power to take peace from the earth and to make men slay each other. To him was given a large sword.

//We continue our historical-critical discussion of the Revelation’s four horsemen with this, the second of four. This horseman, like the other three, relates to the events of the Jerusalem war in 70 A.D.

There is little to say about this horseman except the obvious: red denotes bloodshed. Its rider steals peace from the earth, which refers to the breaking of the Pax Romana, the “age of peace.” Augustus ushered in this time of peace over 80 years earlier, though Origen would later claim that Christ initiated this period with his birth.

But now, war dramatically shatters the peace in Judea. Jewish historian Josephus writes, “[T]he daytime was spent in shedding of blood, and the night in fear.” He estimates nearly 1.2 million Jews perished in the Jerusalem war, most in the final bloodbath that concluded with the destruction of the Temple. Roman historian Tacitus would say only half that many died, which sounds a bit more reasonable, but Josephus’ number shouldn’t be entirely discounted, because the final siege began at the feast of the Passover, when great multitudes of Jews came to worship–for six hundred years, the Passover lamb had always been slain in Jerusalem. By the end of the war, around the Temple mount, according to Josephus, “the ground did nowhere appear visible, for the dead bodies that lay on it.”

Book review: Tomorrow’s God

by Neale Donald Walsch

★★★

Not my favorite from Walsch. Walsch is the author of the Conversations With God series, and this book reads similarly.

They were not looking at the world around them.

…and so it begins, as God talks his way through our misconceptions about him in part one, and how a new vision of God will help us create a newer, better world in part two. A world where bickering over methods of worship is behind us, where harmony becomes mankind’s purpose, and humanity can work together in love. From the back cover: In Tomorrow’s God, Walsch offers compelling reasons why adopting this new belief system is in the best interests of humankind–now.

God turns out to be a bit long-winded. A hundred pages was enough for me, after which I grew thirsty for more than a spiritual guide. As wonderful as this book’s teachings are—and, honestly, to be fair, they are—it wore me down to be constantly talking to a being of Walsch’s imagination. More facts I could sink my teeth into, less God-talk, and I could happily develop my own “belief system” instead of “adopting” Walsh’s. (Does anybody really just select a belief system like a box of cereal at the supermarket?)

I’ll try reading the book again in a few years and will probably develop an altogether different opinion.

Revelation 6:2, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Part II of V

I looked, and there before me was a white horse! Its rider held a bow, and he was given a crown, and he rode out as a conqueror bent on conquest.

//We’re discussing the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, and their probable original meaning as they relate to the time of John of Patmos. This verse introduces the first of the four, riding a white horse.

This horseman speaks of a warrior, “bent on conquest.” Because of the color of the horse, many interpreters imagine the horseman to be Jesus himself. Jesus arrives later in Revelation riding a white steed. But Jesus just doesn’t jibe with the atmosphere of the other three horsemen. These horsemen appear like four faces of evil.

In this light, many have wondered if the white horseman intentionally mimics Christ. Could he be the Antichrist? No, that doesn’t quite fit either. You may be surprised to learn that Revelation never once mentions an antichrist; only a “Beast of the Sea,” which later became associated with the Antichrist, or the Son of Perdition. But the white horseman seems in no way related to the Beast.

Who, then? In light of Revelation’s description of the war of Jerusalem in 70 A.D., one name stands out above all others. Vespasian, the Roman general who stormed through Galilee and Judea terrorizing villages as he approached Jerusalem. The Jewish historian Josephus proclaimed Vespasian the Messiah, so John of Patmos seats him on a white horse, mimicking Christ, the true Messiah. Vespasian also imitated Christ as a healer: healing a blind man with spittle, a lame man, and man with a withered hand. These events would have occurred around the year 69 or 70, about the time Mark penned his Gospel describing how Jesus performed exactly the same miracles.

John tells how this horseman was given a crown, and how he rode out as a conqueror. David Aune, author of three scholarly tomes on Revelation, suggests that a more accurate interpretation of today’s verse may be “the conquering one left to conquer even more.” As history buffs already know, Vespasian did just that. Bolstered by Josephus’ vision of him as Messiah, Vespasian broke off the attack on Jerusalem (handing it over to his son, Titus) and returned to Rome, to claim by force an even greater place. He was crowned king over the entire Empire.

More about Vespasian’s role in Revelation can be found in my book, http://www.thewayithappened.com

Got an opinion? 0 commentsBook review: Why God Won’t Go Away

by Alister McGrath

★★★★

McGrath comes out of the gates with guns blazing against the New Atheism. He’s a debater, having met Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, and Christopher Hitches in debates, and his competitive stance shines through. He refuses to meet atheists on their level, insisting that “faith doesn’t contradict reason, but transcends it.” Questions such as, “What are we all here for?” and “What’s the point of living?” are legitimate questions, and we’re right to seek answers to them, but science isn’t going to help.

There are three parts to the book:

Part I: McGrath discusses the New Atheism and its major proponents, giving a brief description of the work of Harris, Dawkins, Dennett, and Hitchens. The New Atheism, he explains, is about more than promoting disbelief in God. It’s about intolerance of religion completely. It is aggressive anti-theism. For many, the New Atheism has become arrogant and increasingly disconnected from the real world.

Part II: McGrath puts his research to work against the New Atheism, concluding that: (1) Atheism has simply failed to make its case that religion is necessarily and uniformly evil. (2) Belief is actually quite rational. Some of the arguments here are quite interesting, and I’m still contemplating their validity. (3) Science is inherently limited in what it can prove. McGrath quotes Stephen Jay Gould as saying, “Science simply cannot (by its legitimate methods) adjudicate the issue of God’s possible superintendence of nature. We neither affirm nor deny it; we simply can’t comment on it.”

Part III: A short little section about the New Atheism’s future that’s worth reading if only for its humorous conclusion.

The book is definitely engaging, if a little frustrating because of its limited focus. Let’s be clear on what this book is not. It is not an argument for the existence of God. McGrath never once defines what he is defending–the entire point of the book seems to be to discredit the New Atheism–so I’m hoping this book was meant to lead into his 2011 book, Surprised by Meaning: Science, Faith, and How We Make Sense of Things. I’ll see about getting a review copy of that one.

In the mean time, I’m left hanging. If I reject atheism, what am I supposed to replace it with? There is, for me at least, a vast difference between accepting the possibility of a divine creator and believing in that creator. Then, there is a vast difference between believing in a creator and assuming the God of the Bible is that creator. Finally, there is a vast difference between believing that Bible writers have found God and believing that the Bible is the Word of God, endorsed by God Himself. So, we’ll hopefully see where McGrath goes with this in his next book.

Revelation 6:1-8, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Part I of V

I watched as the Lamb opened the first of the seven seals.

//In Revelation chapter six, a mysterious scroll is slowly opened, as Jesus removes seven seals from the scroll one at a time. As each seal is removed, Revelation’s story directs us to the earth and the events happening there. I briefly introduced this mystery scroll in a post a few days ago.

The first four seals serve to introduce four horsemen. This image of terrifying warriors riding horses of four different colors has fascinated artists, storytellers, and hellfire preachers for two thousand years. But what do you suppose John of Patmos was originally writing about, way back in the first century? Let’s take a closer peek at these four horsemen, and see if we can make sense of the images from a first-century perspective.

Scholars have long recognized the unmistakable similarities between the images used here in the seal-breaking and the Olivet Discourse in Mark 13, Matthew 24, and Luke 21, where Jesus predicts the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in 70 A.D. War, international strife, famine, and earthquakes occur in the same order in both the Gospels and Revelation. Luke specifically names Jerusalem as the city under siege, and nearly all Bible interpreters agree that the Gospels, all written after the war began, “predict” the war of 70 A.D. These Gospel accounts, often termed the “little apocalypse,” mirror Revelation in other ways as well:

- The Gospels and Revelation both speak of the Abomination of Desolation.

- Both speak of the gospel first being preached to every land.

- Both speak of the Great Tribulation.

- Both say false prophets will arise.

- Both mention the Son of Man arriving on the clouds.

- Both mention a trumpet sounding the end of all things.

- Both mention a darkened sun and moon and stars falling from heaven.

- Both describe birds feeding on the carcasses of the dead.

- Both were to be fulfilled “soon.”

How have we come to believe the Gospels speak of a different event than Revelation? Surely, as John penned his frightening story of four horsemen, he had in mind the events of his day. The “big apocalypse” of Revelation could only be the “little apocalypse” of the Gospels. Over the next four posts, I’ll describe these four horsemen and their role in the first century.

Book review: The Dark Side of Christian History

by Helen Ellerbe

★★★

This is a rather discouraging look at Christianity through the last 20 centuries. The book’s value is not in the strength of its research (which is one-sided and sometimes shallow) but in its provocative imagery. You won’t forget it. “The Church had a devastating impact upon society,” Ellerbe insists at the beginning of chapter four as she dives into the dark ages. While historical atrocities such as the crusades and the Inquisition are indeed embarrassing to the Christian side of the ledger, one gets the sense from this book that Christianity is at the root of racism, illiteracy, poverty, plague, violence, slavery, and everything else wrong with the world.

Do not imagine you are reading a book about Christian faith; Ellerbe’s focus is on the human abominations done in the name of religion, not on its creeds or principles. We all know that the example Christ left was one of nonviolence. Ellerbe’s take is not that Christianity is evil in itself, but that monotheistic religion is flawed, and simply cannot produce positive results over the long haul. A monotheistic religion naturally leads humanity to the “dark side.”

Ellerbe’s bias is easily detectible. She does, however, make some intriguing points and provide some graphic examples, not least of which is the treatment of accused witches, whose emphasis within the book is probably no coincidence. Though not clearly stated (or so I didn’t notice), Ellerbe’s religious sympathies appear to lie that direction; she bemoans Christianity’s “alienation from nature.”

The horror of witch hunts knew no bounds, she says. “Sexual mutilation of accused witches was not uncommon. With the orthodox understanding that divinity had little or nothing to do with the physical world, sexual desire was perceived to be ungodly. When men persecuting the accused witches found themselves sexually aroused, they assumed that such desire emanated, not from themselves, but from the woman. They attacked breasts and genitals with pincers, pliers and red-hot irons.”

Read the book for an eye-opening overview of the topic, but with a little grain of salt.

Genesis 49:29, Gathered To My People, Part II of II

And he charged them, and said unto them, I am to be gathered unto my people: bury me with my fathers in the cave that is in the field of Ephron the Hittite.

//As described a couple days ago, Abraham held no dream of a resurrection. His expectations beyond death were to be “gathered to his people.” But no explanation of this phrase is given. If Abraham gives no hint about his afterlife expectations, then what about his grandson, Jacob?

Today’s verse provides the answer. When Jacob dies, he doesn’t look forward to living with God. Jacob is terrified of heaven. One day, in a dream, he sees angels traversing a stairway up and down to heaven, and he is afraid, having discovered the doorway to the realm of God. No, Jacob just wants to be buried with his grandfather. Until very late in the development of the Old Testament, that was the best one could hope for after death; for your bones to be reunited with the bones of your fathers. Jewish identity, then and now, is rooted in ancestry, with the desire to be remembered among your offspring.

Even in the second century, B.C., after Jews began to believe in an afterlife, resurrection didn’t mean heaven. A friend asked me a few days ago when Christians began believing in heaven. Not just an afterlife, but a belief in living “up there” with God. I just don’t know! Part of the problem is that the Greek word for heaven is also the Greek word for sky. Our picture of heaven is so far removed from how it was pictured in Bible days that this is a difficult question to answer. When did heaven become more than just layers of sky? Revelation, which most consider the ultimate description of life after death, was not originally about heaven at all. It was about living again on earth. Paul, who helped integrate the Greek concept of the soul into Christianity, dreamed of floating about in the sky like Jesus, but not as a bodiless spirit. I do wish we had more of Paul’s letters than the few that were collected and preserved; he’s an absolutely fascinating theologian, and could probably shed a lot more light on the topic.

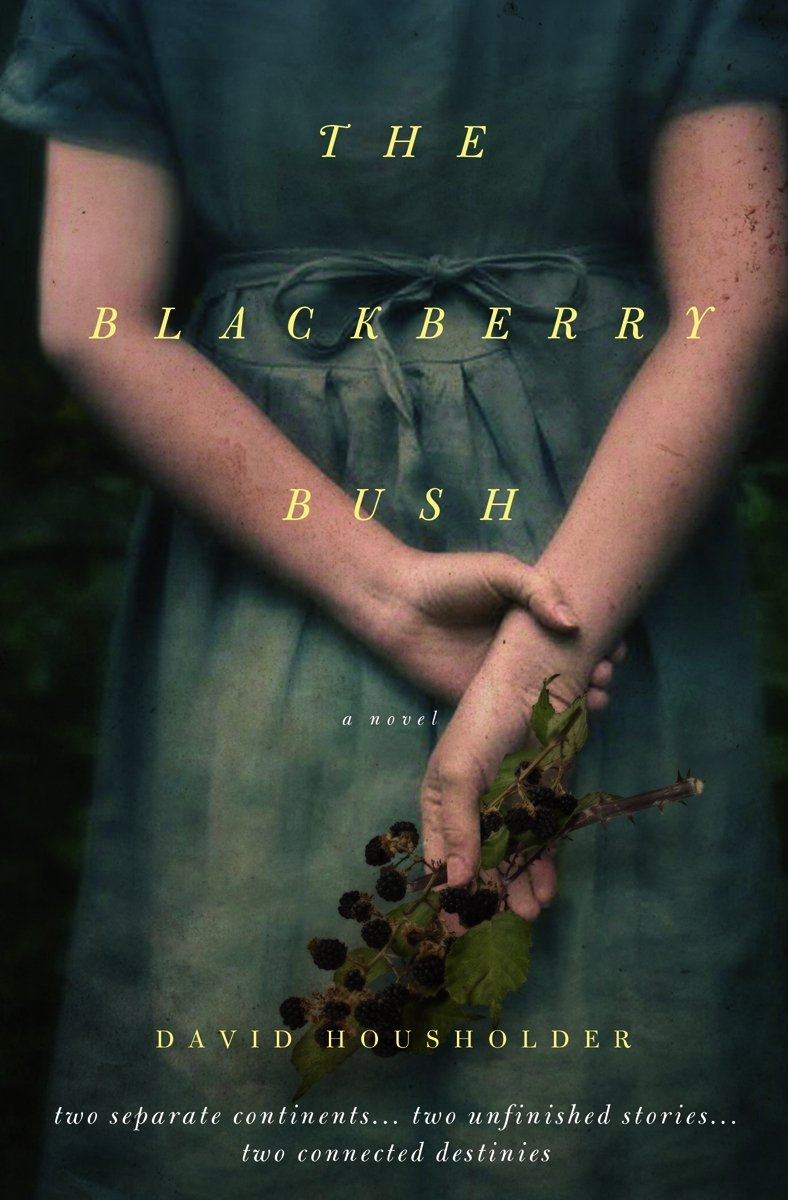

Got an opinion? 2 commentsBook review: The Blackberry Bush

by David Householder

★★★★★

I have strong feelings about this book. I just don’t know what they are. I must endorse it, because it’s unforgettable.

The Blackberry Bush was authored by a Facebook friend, whom I picture as a conservative “Christian teacher-leader” (David’s words) living 2,000 miles away. I’m not sure “conservative” is how David pictures himself, so I’ve probably already insulted him. And I’m not much of a fiction reader; this will be my last for a while—I’m burned out. But on a whim, I asked for a copy. David turned out to be quite insightful, and a superb fiction writer besides!

The two main characters, a boy and girl growing up on opposite sides of the world, are quite vivid. You’ll identify with one or the other, and possibly both. They are both very real—very real!—and what troubles me most about the book is that I dislike one of them. I don’t want to, and I don’t think I’m supposed to, but I do.

I can’t describe the emotional journey, so I won’t try. Just read it, and let yourself be immersed in feeling; it might change your view of life. The book is more spiritual than Christian, so it won’t change your life that way. It’s certainly not going to talk you into a church building. I’m not really sure “spiritual” is even the right word. Honestly, I can’t put my finger on the feelings it evokes, but there is one word at the root of it all. A word with many definitions, all of them lacking. That word is Faith.

I wish the book were true. I wish all that’s wrong with this screwed-up world could just work itself out, like a rubber band unraveling under its own pressure, perhaps with a little karma, or predestination, or meddling from above, or an intertwining of energies, or whatever your religious bent is, leaving everybody happy in the end. But life is messier than that, and the kinks don’t always get worked out. There’s no guarantee of happiness. So where does that leave faith? Faith certainly isn’t wishing, nor is it holding hands and singing Kumbaya. But whatever it is, David’s book will strengthen yours.

The author thinks this would be a good book for teens and book clubs. Ahh, what do authors know, he’s flat wrong. It’s for parents and grandparents.

354 Circles

354 Circles

603 Goodreads Friends & Fans

603 Goodreads Friends & Fans

Hello! I'm an author, historical Jesus scholar, book reviewer, and liberal Christian, which means I appreciate and attempt to exercise the humanitarian teachings of Jesus without getting hung up on any particular supernatural or religious beliefs.

The Bible is a magnificent book that has inspired and spiritually fed generations for thousands of years, and each new century seems to bring a deeper understanding of life’s purpose. This is true of not only Christianity; through the years, our age-old religions are slowly transforming from superstitious rituals into humanitarian philosophies. In short, we are growing up, and I am thrilled to be riding the wave.

I avidly read all thought-provoking religion titles. New authors: I'd love to read and review your book!

Hello! I'm an author, historical Jesus scholar, book reviewer, and liberal Christian, which means I appreciate and attempt to exercise the humanitarian teachings of Jesus without getting hung up on any particular supernatural or religious beliefs.

The Bible is a magnificent book that has inspired and spiritually fed generations for thousands of years, and each new century seems to bring a deeper understanding of life’s purpose. This is true of not only Christianity; through the years, our age-old religions are slowly transforming from superstitious rituals into humanitarian philosophies. In short, we are growing up, and I am thrilled to be riding the wave.

I avidly read all thought-provoking religion titles. New authors: I'd love to read and review your book!

Hi! While Lee writes the articles and reviews the books, I edit, organize, and maintain the blog. The views expressed here are Lee's but I'm his biggest supporter! :-)

Hi! While Lee writes the articles and reviews the books, I edit, organize, and maintain the blog. The views expressed here are Lee's but I'm his biggest supporter! :-)

Connect With Me!